|

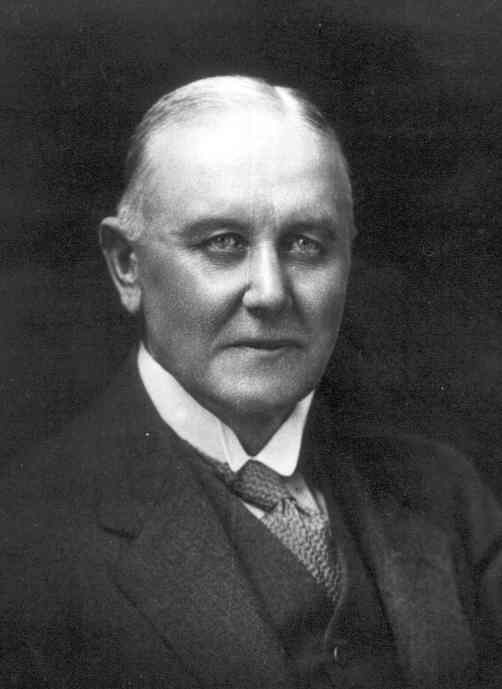

Frederick Ratcliffe Riley

F. R .RILEY -- Surgeon Frederick Ratcliffe Riley (1865-1932) known to his students in his later years as Father Riley, was born at Barnstaple in Devon, the birthplace of so many who have wandered abroad seeking fresh horizons. Born into the home of a civil servant of modest means he obtained some of his early education at Hayes Grammar School, Middlesex and then at The Grammar School, Eye, in Suffolk, where his headmaster in his final report stated, "...general conduct excellent,... in studies facile princeps". From school he entered the London Hospital as a medical student qualifying in 1890 just one year behind Wilfred Grenfell whose friendship and example influenced the life of the young Riley. Of his teachers at the London, the famous Sir Frederick Treves, Surgeon General to king Edward VII. Was the teacher whose inspiration steered the youngg student into surgery so that later on, in 1896, Riley was to be admitted as a Fellow of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. At the London, where he was regarded as one of its most distinguished students, he received many prizes and awards including the Obstetric Scholarship and testimonials given him on his departure indicated even then not only his ability as a surgeon but his conscientious nature, his kindliness and his courtesy. On completion of his term as a house-surgeon Riley, following the example of Grenfell, sailed with the North Sea trawlers as surgeon to the Mission for Deep Sea Fishermen. In this service he learnt at first hand of the hardships and tragedies that were the life of the underdog. In 1892 in answer to a call from his brother Arthur, he sailed for New Zealand where he worked as locum tenens for his brother and soon succeeded him in a general medical practice at- Winton in Southland. At that time the Winton doctor was the only one between Queenstown and Invercargill. His varied and often exciting duties took him far and wide on foot or on horseback, in a horsedrawn buggy or by railway jigger. Riley used to describe to his family a journey that he made one dark stormy winter's night on horseback in answer to an urgent call to the bedside of an elderly woman who had swallowed her false teeth and was believed to be in imminent danger of choking to death. The story would reach a climax, “What did you do?" a wide-eyed family would ask. A smile would spread over his face and his watery blue eyes would light up “I found the denture under the bed !” |

|||||||||

| Father | |||||||||

| William Mumford Riley | |||||||||

| Mother | |||||||||

| Caroline Budd | |||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||

|

Charlotte Susan Graham

|

|||||||||

| Children | |||||||||

| Betty Graham died young | |||||||||

|

Frances Melville

|

|||||||||

|

Peter

William Stuart

|

|||||||||

|

Charles Graham

|

|||||||||

|

Jean Margaret

|

|||||||||

|

Complete Family List |

|||||||||

|

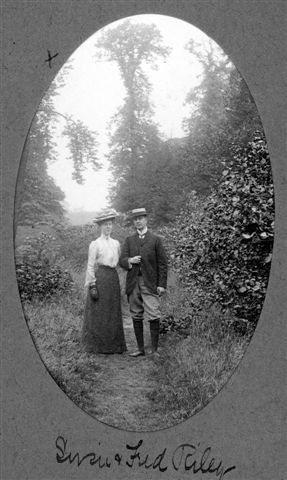

After several years of practice at Winton, Riley moved to Dunedin, where in 1902 a t the age of thirty-seven he married Charlotte Susan, daughter of magistrate C.C. Graham. The wedding at All Saints' Church was conducted by the Reverend A.R. Fitchett, later Dean of Dunedin, and the father of F.W.B. Fitchett who was to become Professor of Clinical Medicine and physician colleague of Riley at the Otago Medical School. In Dunedin he could now develop more readily his surgical talent both in private practice and as a surgical tutor at the Medical School. He was appointed Obstetrician at St. Helen's Hospital when it was opened, on 30th September, 1905, by Mr. R.J. Seddon M.P. In 1909 he became a member of the Honorary Medical Staff of Dunedin Hospital, a position that he held until his death twenty-three years later. His real interests however, were people and above all the problems of childbirth, and he soon established a practice in obstetrics and gynaecology that covered the whole of Otago. A mother and her child were something for which he had a profound reverence and the rearing of a family he regarded as life's most sacred and satisfying duty. He once observed that "the larger the family the more cheery and happy it seemed …….children are the best insurance against old age, their voices help to renew our youth should any family fall on evil times there is no country where so many hands are stretched out to help" .In discussing the difficulties of rearing a large family in a young country like New Zealand he went on to say " …..it is the fight that develops character….. our best citizens are those who have conquered the difficulties of education and environment. Even if they have not conquered they have been better men and women for the struggle. Riley himself had five children, one of whom died in early childhood. . F.R. Riley the young surgeon, succeeded Ferdinand Batchelor as Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology and then began a long association with teaching of students and instruction in the art of midwifery and the performance of innumerable operations for women's complaints. His associates in these onerous part-time and largely voluntary activities were his contemporaries, Russell Ritchie and Charles North, his younger colleagues Roland Fulton and James Jenkins as well as a band of devoted nurses at the Batchelor Hospital, St. Helen's and the Public Hospital. Obstetric practice in those days made great demands on a medical man who was called upon to combat the three great calamities, haemorrhage, puerperal sepsis and eclampsia. Blood transfusion was in its infancy, there were no effective anti-bacterial agents and eclampcia was ill understood. The three side wards in the old Batchelor Hospital were continuously filled by women suffering from pelvic sepsis. Much of the teaching of obstetrics has since changed so that many of the systematic lectures of that day are now outdated and much of the detailed teaching of pelvic disproportion in relationship to childbirth is no longer necessary. Gynaecology has on the other hand not changed so much although techniques have improved and early anti-biotic treatment of gonorrhea in the female has eliminated much of the pelvic inflammation for which surgery was often the only cure. All this work had to be fitted into the busy life of a vast general and surgical practice --a practice in which Riley's special gift of understanding was in constant demand. Teaching conditions were then undoubtedly primitive. Facilities in the Medical School and in the maternity hospitals suffered from lack of funds and there was also a limit to the amount of time which a devoted band of teachers could give to instruction. That they turned out so well a generation of New Zealand doctors says a great deal for their precept and example. During the last few years of his life his over-sensitive nature made him feel deeply the criticism of the teaching of obstetrics and gynaecology that was an inevitable accompaniment of the nationwide appeal for funds to provide for the establishment of a full-time chair of obstetrics and gynaecology. That criticism came loudest from some for whom he had the greatest affection and respect hurt him all the more and his election in 1927 as a Foundation Fellow of the newly formed Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and also his last minute elevation to the rank of Professor were insufficient to remove his hurt. However, the replacement of part-time teachers by full-time heads of departments was an inevitable step in the development of the Medical School and one that was soon to affect other departments too. Apart from his practice, his voluntary hospital work and his teaching, Father Riley made time for a variety of other interests. He was elected a member of the City Council but soon relinquished this position when he found it too time consuming. He contributed little to its policies and in fact the Mayor of that day H.L.Tapley is said to have facetiously commented "Riley's major contribution was to move an adjournment” He had a fondness for pictures and during his lifetime acquired a number of fine paintings and engravings. He was also an enthusiastic photographer who would proudly show to his close friends albums containing photographs taken in many parts of New Zealand with the aid of a cumbersome brass- bound half-plate camera. Especially interesting were the carefully composed photographs taken during a trip on horseback made in the early 1900’s. His companions were two of his oldest friends, the small but energetic E.E. Blomfield also a distinguished graduate of the London and fellow lecturer at Otago, and the Reverend James Aitken, a tall bearded fine-looking figure one of whose two brilliant sons was to become Vice-Chancellor of Otago University and is now, as Sir Robert Aitken, a university administrator of international repute. On their journey from Wanaka to the West Coast over the Haast Pass track Riley nearly lost his life. His horse, losing its footing, suddenly began to slide down a steep slope and its rider only had time to throw himself clear as the horse, gathering momentum plunged to its death in the beech forest below. At "Opeke" his country home near Waitati, he displayed paintings of early Dunedin, a set of Sapper Moore-Jones' Gallipoli water-colours, old English etchings and engravings and some of H.G. Ponting's famous Antarctic photographs. Occupying the place of honour above the sitting-room fireplace in which the spruce logs burned was his favourite, the well-known engraving entitled "Blind Man’s Bluff". His Maori artefacts and his collection of books on early New Zealand revealed his intense interest in Maori history and it was fitting that his widow should have presented the artefacts to the Otago Museum for the benefit of the city of which he was so proud. He came from a deeply religious family whose depth of feeling was such that they had left the Anglican Church for the Presbyterian on account of the latter's more liberal views on the admission to the communion table of the adherents of other denominations. Riley had his family pew in Knox Church, Dunedin, a church which he served for many years as an Elder. After his death the Reverend D.C. Herron likened him to Barnabas "who exercised the grace of encouragement". The Minister went on to say, "the influence of this fine Christian character enriched many a life, inside and outside Knox Church" . On the annual Hospital Sunday when special services were held in many Dunedlin churches, he obeyed a deep ecumenical urge when he made a practice of attending both a Presbyterian and a Roman Catholic Church. Father Riley loved his home and his family though his reserve and the weight of other peoples burdens prevented him from establishing as perfect a relationship at home as might have been expected. However, in his home at 6 Pi tt Street and later in the former Knox Church Manse in George Street, his wife and he presided at many a dinner party of close friends. On Sundays a formal midday dinner -roast sirloin of beef with horse-radish sauce and Yorkshire pudding, followed by his favourite apple dumpling was prepared by Nellie, a Scottish cook and served by Isobelle, a young uniformed housemaid. On these occasions he would offer his guests light wine or Speight's ale and enjoyed it himself although he always voted for prohibition because he was prepared to give up this pleasure for the good of the country as a whole. His early observations in the North Sea had led him to regard alcoholic liquor as a potential social danger. Intelligent conversation with touches of humour he enjoyed as much as he disliked petty gossip. Early in their married life dinner would be followed by a round of songs in which his bass voice provided a useful background. Many well-known persons came to the house including Truby King, founder of the Plunket Society, for whose work Riley had the profoundest admiration. Father Riley enjoyed perhaps more than any the dinners to which were bidden his house-surgeon from the hospital. Many who are today themselves senior members of the profession will remember his kindly interest in them, not only at Sunday dinner but when they were struggling to establish themselves in practice. As he prospered so he acquired properties in the country. He loved New Zealand, its sea shores and mountains, its blue lakes and forests. “Opeke" on the edge of Blueskin Bay at what is now knowm as Doctors' Point he bought from Michie, the original owner of this beautiful 30 acre property. Here he would join his family when time permitted. He would love to don his thigh-waders, run his clinker-built dinghy into the bay and net flounders while the tide was out. He rowed powerfully, correctly feathering his oars as became a member of the London Hospital Rowing Club's champion fours and pairs. Clipping hedges, scything long grass and sawing wood with his large cross-cut saw he regarded as a past-time. He enjoyed the wind in the pine plantations, the red May in spring, the apple-trees in the orchard and the bellbirds and fantails, silver-eyes and tomtits that sang in the remnants of native bush. On New Year's Eve a huge bonfire would light up the waters of the bay and rockets screamed upwards as an effigy of the Kaiser surmounting the pyre was quickly consumed by the flames. Afterwards songs around the cottage piano arid a toast to the New Year. When he first went there in his 1910 model Rover with its brass acetylene headlamps and canvas hood tied down with leather straps he would wear his flat cloth motoring-cap, a white dust-coat and leather gauntlets. The fourteen mile journey over Mt. Cargill by the rough Junction Road was seldom uneventful. A tyre might burst, or a lamp burn out and on the way home there was the inevitable stop at the water-trough at the top of the hill where a dipper carried for the purpose was used to convey water to an overheated engine which blew out clouds of protesting steam. At Blueskin Bay Riley and his colleagues Fitchett, Batchelor, Williams and Fitzgerald would each year entertain fourth and fifth year medical students at a huge combined picnic. The students were brought from Dunedin in a special carriage of a train that stopped by special arrangement at Michie’s crossing. They would stream off the train in joyous mood, and the day would be spent in boating, fishing, playing tennis or badminton, or just eating and relaxing. Some of the more thoughtful students would spend their time hunting for Maori artefacts on the spit opposite Warrington Beach. A photograph of Father Riley in the centre of a crowd of students taken at one of these occasions in front of Opeke hangs on the wall of the Medical School. At Lake Hawea he bought, in the early 1900's, Timaru Creek Station -rugged mountains along the edge of deep blue waters extending up the Hunter Valley to the main divide. Incomparable rivers teeming with rainbow trout, red deer on every spur, rabbits by the thousand and a comparatively few merino sheep. This was the beginning of what was to become , after Riley's death, a well established high-country station. To Lake Hawea he would take each summer and sometimes in the winter too a party of his friends. He would take his guests up the lake in his launch "Jean Margaret", walk them up the valleys and over the hills, picnic under the beech trees on the silvery shore at Silver Island, picnic across at the Neck or up at the head of the lake. Boiling the billy was a part of the ritual. On one occasion the matches were forgotten. The host sat alternately rubbing two sticks together and focussing the sun's rays with his spectacles so thast just before it was time to set off home he gave a triumphant shout as a small flame appeared and his happiness was complete. Unfortunately he left his glasses behind so that the whole party had to return to the same spot the following day! Many of' his colleagues enjoyed his hospitality at Timaru Creek, amongst them Drennan, Carmalt Jones, Fitchett, Hercus and Bell, names that have been so closely linked with the history of' Otago Medical School. When he and his friends first went to Timaru Creek the journey was a long one. The Central Otago express which took them to Clyde would make a luncheon stop at Ranfurly where hotel and railway dining-room would compete for custom -a waitress in black dress and stiffly starched white uniform would stand outside each place ringing vigorou-sly a large and noisy bell. A night at the Commercial Hotel at Cromwell and a visit to the stone dimly lit huts of Chinese gold-diggers beside the Kawarau would be followed next day by a dusty drive up the Clutha Valley. Andersons' motor-coach with the hood down and crammed with passengers and luggage would sometimes stick in the sand on the outskirts of Cromwell. Morning tea at Queensbury, a call at Mt. Pisa station and lunch at Luggate, an exciting glimpse of the deep blue of Lake Hawea and the snow peaks at the head and then, at last Hawea F1at. A cloud of dust beyond the golden wheat fields would, in summer, herald the approach of the station buggy behind a chestnut pacer and a glossy black mare, Bess, that had once drawn a hearse. An eight mile drive along the east shore of the lake brought the party to Timaru Creek homestead in its shelter-belt of tall gums and pines edged by weeping willows. Riley had many .friends in the district amongst the people who lived and worked in this r-ugged but beautiful lake country; amongst them was the wiry Scot, Dave McCall who lived with his family at Timaru Creek and managed the station in its early years; the Muirs, Buckley and the Hodgkinsons of Hawea Flat, all of them tough independent high-country men. (Graham Riley often reminisced that McCall was known to growl to the Riley boys “You’ll learn from your experience!") Tom Gillespie and his capable hospitable wife, who, with their two children had created a remarkably comfortable yet simple tented home originally far up the Hunter Valley where Gillespie trapped rabbits and shot deer, and later by the foot of the lake. Their camp was a regular place of call for Riley, who admired so much the Gillespies' ingenuity in making their modest home comfortable and their obvious contentment with this simple way of life. In the 1920's Riley also acquired a sheep station in Hawke's Bay. The Hawke's Bay venture was a financial disaster and brought much sadness to its owner who had dreamt of establishing his English relatives on it. His own heavy losses and the repayment of his family's interest in this property were to weigh heavily on him and possibly hastened his death. His love for New Zealand made him resentful of those who tried to despoil it. A letter to the Otago Daily Times signed by F.R. Riley, W.H. Borrie, James Thomson and C.M. Focken, begins "For some time we have. viewed with alarm and indignation the increasing presence of rural advertisements. For miles the exits from all our towns and cities are disfigured by hoardings painted in brilliant and glaring colours shouting the merits of petrol, motorcars, motor-oils, whisky and soap. They are absolutely out of keeping with the charm of our countryside…….why should the country we love so well be so disfigured. ……why should we tolerate it….” These four did not tolerate it. They took axes and saws, cut down all the hoardings between Cromwell and Clyde and heaved them into the Clutha River. In the words of “Sextette” chorus in the 1931 capping concert: Riley the bold and reckless bandit

chieftain, This episode became more than a household joke, it stirred up public opinion and for the next decade the number of road and railway hoardings diminished. His hope was that this battle for his country would be carried on after him. Riley died on 1st August 1932 of a heart attack shortly after an operation. His death came as a shock to the many who loved him and tributes poured in from far and wide . For the Honorary Medical Staff, Dr Fitchett drew up a minute recording the death of their "well beloved colleague, Frederick Ratcliffe Riley......benevolence was the keynote of his nature and benefaction the theme of his daily life…… a man of deep religious conviction who lived his religion……….. a champion of right……………. he pursued his point with an unflagging tenacity which was alike the despair and the admiration of all who differed from him. He burned at the thought of injustice. In an editorial dated 12th August, 1932, an Otago newspaper commented "here was evidence of the well balanced life: he was never righteous overmuch - if his principles were rigid his humour was flexible". There was applied to him as a final tribute R.L. Stevenson's description of a physician "he is the flower of our civilization and most notably exhibits the virtues of the race" .

Graham Riley 1971 |

|||||||||